By Akanimo Sampson

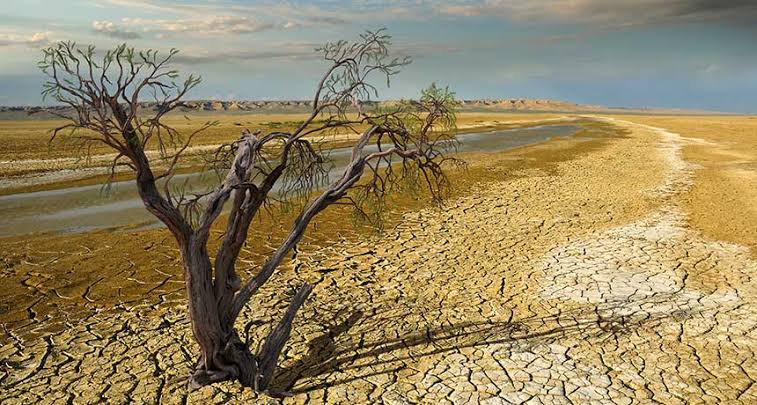

Most of the Kilinochchi District’s 400 irrigation tanks in Sri Lanka have fallen into disrepair due to three decades of conflict in the country. The climate has also changed. While some areas of Sri Lanka experience floods, in others dryness has turned to drought.

It is more than six months since Mrs Murugesu Nagulambigai last saw rain. Her hometown, Arasapuram, in the northern Kilinochchi district, is a naturally dry area and traditionally local farmers coped with the lack of rainfall by irrigating crops from artificial village reservoirs, known locally as “tanks.”

In Nagulambigai’s village the only water source came from one of the tanks. Nagulambigai, 60, relied on it to irrigate her crops and feed her family. But the rivers feeding the tanks ran dry which left them empty for most of the year.

“We own a few acres of land but cropping is futile. There is not enough rain. And too much drought”, she said. “The scorched earth shrivels. And so do we.”

“We have got by on very little income these last few years; and survived on a meagre diet of lentils and rice,” said Nagulambigai, recalling recent seasons. “The land is fertile but not productive for vegetables and paddy. I struggle to gather just a plate of garden greens and other vegetables – luckily some have sprouted through the parched earth – and am only too happy when I am able to find some fish for my sons.”

To address this challenge to local livelihoods, the International Labour Organisation (ILO) mobilised funds, set aside for developing community-owned assets and mitigating climate change, for a project that would renovate the local tanks and provide paid work for local people.

A pilot, the Community-Managed Irrigation Scheme Improvement, was carried out with the technical assistance of Sri Lanka’s Department of Agrarian Development (DAD), Ministry of Agriculture.

Nagulambigai joined the renovation work on the tank in her village. This included de-silting it by 2 feet and using the silt to strengthen the bund wall and surrounding spill by 1.5 feet.

“Men did the heavy work, like pushing rollers to compact the soil, and women helped to re-turf the tank bund. We were paid equal wages for work of equal value”, said Nagulambigai. “This has helped to supplement my earnings and boost family finances. I no longer feel helpless as the sole breadwinner.”

The rehabilitated Arasapuram tank was one of three earmarked for improvement by the district authorities and was selected through several community consultations. The renovations mean increasing the tanks’ water holding capacity. Water can now be pumped throughout the year and more than a kilometre from the tank itself, helping Nagulambigai and her neighbours irrigate their fields.

Now that she has a reliable supply of water, Nagulambigai feels optimistic about growing a broad range of crops, including groundnut, coconut, cowpea, green gram, banana, and chillies. She has planted 120 coconut tree seedlings, which she hopes will produce their first harvest in three years. This diversified, multi-crop approach means multiple harvests every year, and a rising monthly income.

“I have an agricultural plan, and it gives me hope. The land gives me rich dividends. The ILO investment in the water supply is a big asset for us. The tank is no longer only the centre point of our village but now the source of its wellbeing. The tank and its surroundings are back to its past glory, as told in the histories of our ancestors,” said Nagulambigai.