Arnold Udoka, Ph.D

Anietie Usen’s Village Boy is based on the account of what happened to a boy who lost his father at a very tender age. It is the heroic narrative of the vicissitudes foisted on a youthful family by death and the problematic adventures by a youngster and an equally young widow straddling harsh cultural milieux of rural and urban lives where survival is both a matter of self-help and reliance on others as coordinates to locate destiny’s El Dorado.

The resonance of Village Boy is its palpable ubiquitous reality in the Nigerian society that swells the underprivileged demography. This is a 23-chaptered book consuming 192 pages with a foreword by the academic maestro of stylistics and literary criticism, Professor Joseph Akawu Ushie. Usen’s prose stars the protagonist in the adventurous character of skinny, fragile, inquisitive, talkative, tenacious and dream-laden Akan through whose engagements the storyline unfolds.

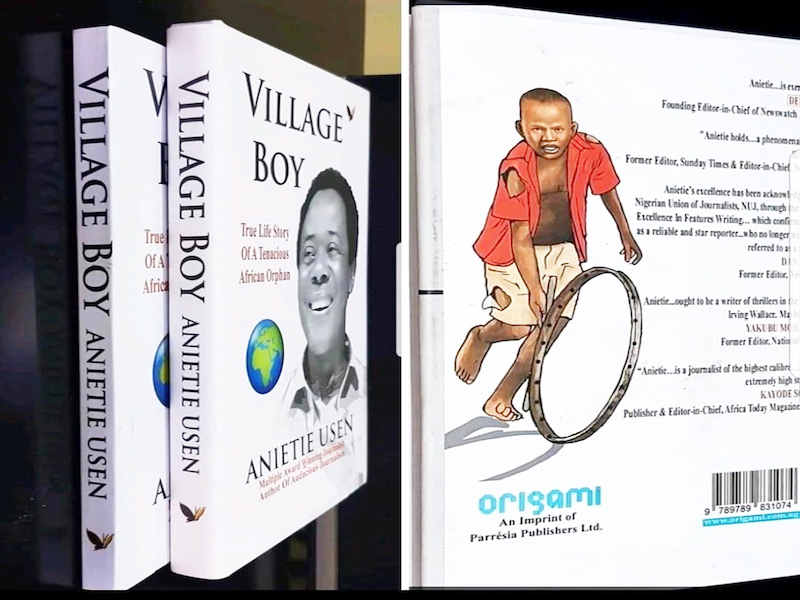

Claiming ownership of the stories the reader is about to experience, Anietie Usen holds forth from the front cover – with a delightful and assuring smile – that the Village Boy is a “True life Story of A Tenacious African Orphan”, extending the circumference of his personal experiences to the aquatic borders of the mother continent as the landscape where more of his kind, who have the same tales as his, can be located. While most consumers of literary writings assume that such works might be improbable and, therefore, purely works of fiction, it is unmistakably true that Village Boy is the mixture of an autobiography and fiction, thus it is classified in modern literature as faction.

The unfolding story is the development of Akan from his formative years to maturity – his moral and psychological growth – thus ascribing the bildungsroman genre to Village Boy. Akan’s development is contemporaneous with the development of the environment he met in Afaha Akpan Iman Ibom as a toddler and wherever he found himself as a mature adult. The book can be divided into topical headings. The first thirteen chapters are themed on village life where the reader is given an understanding of Afaha Akpan Iman Ibom village and its environs with vivid descriptions of the stark realities in a typical Nigerian rural setting of the 1960s.

Chapters 14 to 15 are themed on exposure to other realities. Here, the reader boards a mechanical contraption out of the serene and drab rural cocoon of Afaha Akpan Iman Ibom before daybreak, onto a long route where, “…the trees are running backwards”, until arrival in Aba town where the siren of the train stabs the space with no mercy. The culture shock and the meeting with other relations of Akan’s extended family are experiences to deepen his knowledge of kinship. The exposure to child labour, learning of trades, village games and savagery of houseboyhood are the preoccupations of chapters 16 to 19 set in Afaha Akpan Iman Ibom and Uyo. Akan’s sense of ‘becoming’, are in chapters 20 to 22 where the young man is now a full grown young adult and in total freedom and in full grasp of his destiny.

Read also:

- VILLAGE BOY Wins International Award

- I Have Reversed Rural-Urban Drift- Educationist

- Nigeria Is On Its Knees- Bemoans Ray Ekpu

Chapter 23, a two-sentenced chapter, is an exhortation couched in a paradox urging every individual to break down every barrier of challenge, stand tall and never quit. With poetic titles, a stylistic devise, the opening thirteen chapters introduce the reader to the bucolic and idyllic Afaha Akpan Iman Ibom and its environs in the 1960s and 1970s.

Chapter 1, Footsteps of the Ghost, set in the midnight, portrays the surreal state of affairs in rural Afaha Akpan Iman Ibom where reality and illusion interplay and end on a tragic note. Nnenwa has mistaken the crow of the cock as signal for dawn and walks her two-year old grandson, Akan, to a distant stream in a night cloaked in thick darkness. With an orchestra of noises by animals of various species and an atmosphere peopled by ghosts for company, Nnenwa pays the price for intruding into the world of darkness as she is bitten by a very poisonous snake.

Chapter 2, At the Gate of Heaven, Nnenwa is healed of the snake bite by the herbs she prescribes and unwittingly reveals one of the secrets of her trade as a herbalist to her relations.

Chapter 3, Birthplace of Hunters, Usen takes the reader through Nnenwa’s proficiency in the local midwifery which makes her mud house a maternity of sorts where women are delivered of their babies. He captures the success of the proselytisation into Qua Iboe Church as Grandma, a convert, identifies herself with the Christian name of Maggi Inyang, to invoke the name of Sikofa (the Afaha Akpan Iman Ibom adulteration of the word Jehovah) to intervene as the childbirth process gets beyond her time-tested expertise and herbs. The song of insults by women to their husbands to check male misdemeanours and misbehaviours and the social role of ikprekata, the night masquerade – the dreaded village social media with knowledge of every hidden secrets – forms part of the narrative here.

In Chapter 4, A Castle in the Jungle, Usen brings the reader face to face with the local architecture where, “Red mud and stakes made up the walls. Roofs were made from leaves of palm leaves stitched and stapled together with shafts to form a roof mat. No ceiling. No plaster” (pp 24-2 6). This serves as the humble abode Grandma and Akan share with goats, chickens, rats, jiggers, heaps of palm kernel and akpaisong (ants). Raw food is in abundance and so too are chores. A poorly thatched roof that leaks when it rains and the struggle to collect the dripping water from several roofs paints the stark picture of bare-bone poverty in the household of Grandma.

Chapter 5, Rats for Peppersoup, is where Akan’s story of the place of his birth is revealed and the circumstances that led to his presence in the village. The death of Tim, his father in a ghastly motor accident in Lagos led to his relocation at about two years of age with his younger one to Afaha. Again, he loses the younger brother to death and he begins his life with friends within his age bracket. At about ten years of age, with Imoh and Udoma his cousin, he learns the secrets of hunting, digging up giant rats and setting traps for small and medium sized animals- the pastime and skill acquisition common in rural communities.

In Chapter 6, Barbecue of Termites the termites and bull cricket as part of Akan’s and the village’s cuisine. With containers of water to trap the termites, everyone enjoys eating it raw, fried or cooked; a delicacy everyone looks out for when it is the season. Bull crickets are more delicious but require a lot of work to ensure its wings are the first target to incapacitate the poor creature. Akan has honed his cricket hunting skills.

Chapter 7, The Vernacular of Lizards, Akan learns from Grandma, as all rural children do during storytelling sessions in the night, the philosophy of survival in the fable of the lizard, a giant rat and hunters, as well as from the story of the baby mosquito. All these stories are strategies for uploading lessons in Akan’s memory bank for self preservation, temperance and how to relate with peoples generally.

Chapter 8, A Tale of Two Uncles, the contrasting characters of Akan’s uncles, Etim and Ekong. The former, kind, helpful and approachable and the later, wild, vindictive and beats Akan mercilessly always. Uncle Etim is helpful in teaching Akan by generating the vernacular equivalents of objects in English. He is also good at fables including that of Amedika (America) and pretends to know the taste of every edible thing. But uncle Ekong, Akan’s senior uncle, is the opposite. He is trauma personified. He once beat the young Akan black and blue. In any case Ekong, is not a likeable person in the entire village. Ekong uses all his nephews and nieces as punch bags. This is a dilemma for Akan. Ekong causes the relocation of Akan and his mother to the maternal grandparents’ home. Some uncles with knuckles one would say.

Udoka is a Scholar-Artiste, Choreographer, Writer and Winner 2010 Association of Nigerian Authors NDDC J. P. Clark Drama Prize and Nominee 2014 NLNG Literature Prize.

To be continued

1 Comment

Pingback: Review of Village Boy (2) - StraightNews