By Akanimo Sampson

Alleged unwholesome activities of a petrochemicals corporation operating in Rivers State, Nigeria’s oil and gas capital are fueling a disturbing unease in Eleme local government area of the big oil-polluted state.

Indorama Eleme Petrochemicals Limited is being accused by her host community of employing divide- and- rule tactics in dealing with the people of Eleme, the host community. The situation there has put members of the community at loggerheads with one another.

In early colonial records, according to Wikipedia, Eleme was called Mbolli. The name came from the slave merchants of Arochuku who used the words Mbolli Iche which is said to mean “one country that is different’’ in Ibo language to describe the Eleme people. When the British colonising force entered Eleme in April 1898, their escorts introduced the people to the British as Mbolli people.

Wikipedia says linguistically and ethnographically the Eleme Kingdom is a separate entity from the Ogoni, their neighbours. ‘’Eleme language is very distinct, though phonetically sounds like Ogoni Language, and this has raised the debate over whether or not Eleme is part of Ogoni. Nevertheless, Eleme is not part of Ogoni. Eleme is a unique ethnic group, and the people of Eleme have their unique way of doing things’’, the free encyclopedia says.

The Eleme people, however, live in 10 major towns situated in the local government area, around 20 kilometres east of Port Harcourt, the state capital. The towns are Akpajo, Aleto, Alesa, Alode, Agbonchia, Ogale, Ebubu, Ekporo, Eteo and Onne.

The total territory occupied by the Eleme people expands across approximately 140 square kilometres. Eleme is bounded in the North by Obio Akpor and Oyigbo, in the South by Okrika and Ogu Bolo, in the East by Tai and the West by Okrika and Port Harcourt.

The President General of the Eleme People’s Assembly, Chief Israel Gomba Abbey, is alleging that Indorama Eleme Petrochemicals Limited and other companies in the area have succeeded in creating more impoverished people in the community which is housing scores of companies rather than affecting their lives positively.

Abbey is accusing Indorama, the core investor in the Eleme Petrochemicals of allegedly fueling underdevelopment in Eleme and also operating in the area without a Global Memorandum of Understanding (GMoU) like the Anglo-Dutch oil and gas major, Shell.

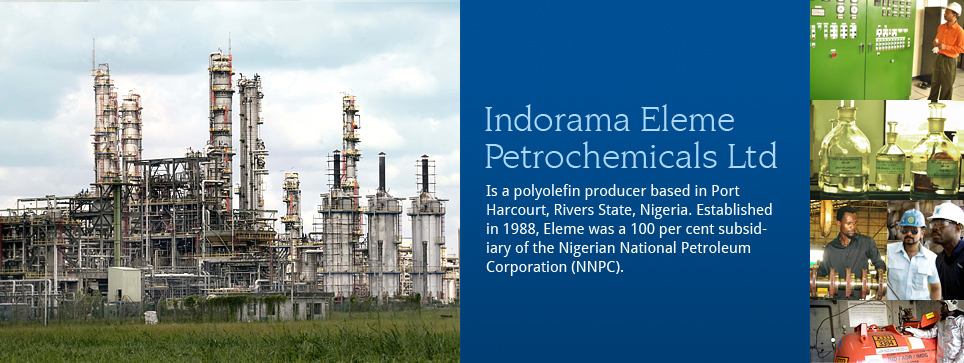

Indorama Eleme Petrochemical Limited (IEPL) is a Group Company of Indorama Corporation, a Poly-Olefins producer of a range of Polyethylene and Polypropylene products. It was a 100% subsidiary of Nigerian government owned Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) with the name Eleme Petrochemicals Company Limited (EPCL).

When the erstwhile EPCL was privatised, under the privatisation programme, the Indorama Group emerged as the core investor and acquired the unit in August 2006. Since then, IEPL has recorded several achievements of smooth and stable operations, enhanced production capacities, winning of several global awards and certifications and has become a successful model of the Nigeria’s privatisation programme.

The Indorama Eleme Petrochemicals plants are operating within the Indorama Complex which is a sprawling 400 acres asset located in Eleme at the outskirts of Port Harcourt. The complex was built by a consortium comprising of Chiyoda Corporation, JGC and Kobe Steel of Japan, Tecnimont of Italy and Spie Batignolles of France.

The complex has state of art Olefins plant, Polyethylene/Butene and Polypropylene Plants, The operations are well supported by a captive power plant, utilities, effluent treatment plant, storage tanks, bagging, warehouses and other supporting facilities. A PET plant was commissioned in July 2012, followed by the world’s largest single train Urea plant in 2016 in the same complex.

Abbey is also claiming that Eleme is at risk of extinction as their other neighbouring towns like Okirika and Ogoni are allegedly trying to annex them if nothing positive was done to develop the area, maintaining that their underdevelopment stems from a lack of purposeful leadership in the area.

While specifically lampooning Indorama which according to his operating in Eleme without memorandum of understanding with the people, he added, “we don’t have a GMoU with Indorama. There is none, ask Indorama if they have any binding document with Eleme people.

Indorama should be open to me and my members. They should open their doors to us, we are not police people, and we are not tax collecting agents but friendly host community member. We have chosen the part of dialogue as it is better to jaw, jaw than war, war.’’

Recently, the Eleme Local Government Chairman, Philip Okparaji, has warned Indorama of dare consequences should they continue to allow their customers’ trucks block the road thereby causing untold hardship to commuters using the road.

Stakeholders are also attributing decaying state of the Aleto bridge to the parking of trucks along the bridge by customers doing business with Indorama.

Oue of the frequent road users, Mike John, who works in Onne said, “I am a regular user of this road; what one goes through around Indorama is terrible. A journey of 30 minutes takes more than two hours because of traffic hold-up. It is becoming unbearable

“This is what we suffer most of the times. Is it that Indorama can’t work with Eleme Local Government to finding a lasting solution to this by securing a parking space? The company is just there to worsen the plight of the people for their own selfish gain.’’

While the spokespersons for Indorama were not eager to comment yet on the issues the community is raising, Abbey however, pointed out that the corporation has succeeded in honouring them through Elano Investments ‘’But this is not enough because the Supreme Court in its 1958 judgment gave Eleme the right as the custodian of all the lands in Eleme and not to a particular community.’’

He is then wondering why Indoroma should shut their doors to the majority of Eleme people “who have us as their community representatives,’’ regretting that all efforts to reach Indorama have been rebuffed.

That is not uncommon with companies operating in the Niger Delta, Nigeria’s main oil and gas region. They are not accessible to the communities because they operate behind military shield, citing communal disturbances often as the reason why they operate behind closed doors.