Publisher: Parresia Publishers Limited, 82 Allen Avenue, Ikeja, Lagos, Nigeria. 2020

Number of Pages: 192

Author: Anietie Usen

Arnold Udoka, Ph.D

Chapter 18, Sharpshooters and the Hooligans, introduces the reader to sports native to and imported into Afaha Akpan Iman Ibom of the 1960s like ekak, oyo, ikara, nsa isong and backyard football. A lively community with tempestuous youth, Akan soaks in this milieu, but he is not as fierce as Odudu who canes people once he is behind the mask or snatch a football even from the owner in his family house. Akan acquits himself of the character of a bully.

Chapter 19, Runaway Houseboy, serves the reader the story of the long absence of Akan’s mother which suddenly ends as she returns from Igalaland after she worked with some white missionaries. Akan is now contracted by the mother as a house boy to a pharmacy owner whose shop is in Uyo. While the pharmacy owner and wife leave home in the morning to the shop at Udo Street, Barracks road, and their children are off to school, it is the lot of Akan to carry out all the chores in the house. There is no breathing space and time for rest for a boy his age. He endures this for two weeks and then hires a commercial cyclist and returns to Afaha Akpan Iman Ibom to the surprise and chagrin of the mother. The mother’s emotional thrashing is not enough to dissuade young Akan from his mindset of forsaking the calling into houseboyhood with no guarantee for continuing with his education. This forces the mother to send a persuasive letter to five of her late husband’s friends in far away Lagos. The long awaited reply arrives from one man – Uncle Onofiok. He communicates the decision of Akan’s late father’s friends of a full scholarship covering boarding and tuition fees which sees him study at the newly established Apostolic secondary School, Ikot Oku Nsit.

Related topics:

Chapter 20, The Birth of Ambition, Akan touches down at the school and sets a goal for himself: to become a prefect. He nurses his dream which seems to grow wings as he moves farther away from rural Afaha Akpan Iman Ibom to spend holidays with his mother who now works in the big city of Calabar. Akan travels by ferry from Oron to Calabar; hawks bread in the day and kerosene in the night to raise some extra cash for his pocket money and support for school uniforms. On one such hawking trips in Calabar, he stumbles on the public library in where the order is opposed to the street and tranquility reigns; he reaches a decision to read and voraciously too, at least a day every week. It is here he reads, among others, the biography of Thomas Jefferson, the third American President, most of James Hadley Chase novels, Times Magazine and Newsweek. The information at his disposal makes him way above all his mates and beyond class textbooks. Gradually, Akan is beginning to comprehend the difference between government, his best subject at school and media. A good debater, the numero uno goalkeeper of the school and member of other social groups, Akan leads his school’s cultural group to represent to the South Eastern State at the Fourth National Festival of Arts and Culture in Kaduna. Akan’s popularity earns him the nickname, Emperor.

Chapter 21, Dreams Do Come True, is a clear demonstration of the result of having an ambition and working towards achieving it. Little surprise then when the ambition to become a prefect materialises as the principal and the vice principal appear in the assembly to announce Akan as the Senior Prefect. Now, Emperor is crowned Emperor; a double Emperor, that is.

Chapter 22, From Village to Villa, is a tableau of Akan’s academic progress from The Apostolic Secondary School, Ikot Oku Nsit, to the University of Calabar, where he bags a first degree in Political Science. He spends his service year as a Youth Corps member in the office of the Executive Governor of Kano State where his journey into the corridors of power and a career as a budding accidental journalist begins. He rubs shoulders with the men and women of timber and calibre, the high and mighty, caterpillar and bulldozers, socialites and mavericks, heroes and villains, warriors and peacemakers. Akan stays with the lessons from his Grandma and his Maama’s God and knows that he is coming from nowhere to somewhere and with a duty to assist others on the journeys of their destinies.

Chapter 23, Advantage of Disadvantage, the author waxes philosophical. He plumbs the hollow depths of poverty and comes up with the verdict that therein are the seeds, soil and manure for surplus; a paradox supported by the principle of inversion. Markedly, he admonishes that quitting is defeatist in thought, shape and form.

Village boy is a portrait of the harsh realities of existence common in all communities not necessarily in villages. It celebrates the strong will to surmount all odds and attain self development by legitimate means. The title is appropriate as it invokes and connotes remoteness; a space occupied by rural folks and shielded from bustling noise of the city; a mere space faraway from ‘civilization.’ This is the space the author takes pride in and reminds the reader that each one is a product of a certain village.

Village boy is masterfully crafted with the stylistic devise of allotting a title to each chapter. Almost like poetry, the chapters are brief and fast paced and yet each chapter encapsulates the ideas as full and complete stories in themselves. The suspense, metaphors, similes, and intriguing flashbacks and comic relieves deepen the plot of Village Boy and make it an interesting work to read.

The author introduces the reader to some Ibibio names, objects and biological register like Akpan Nko, Etim, Ete Obot; Nwa Udo Udom, nkanya, ayang (though wrongly spelt), mfa, ayod, ikprekata, ndube, akpaisong, idiang, to name a few. The author also takes us to towns like Uyo, Aba, Calabar, Oron, Kano, Lagos as well as continents like Afghanistan, Pakistan, England, United States of America in one fell swoop.

However, Village Boy did not escape the rod of the printer’s devil. There are errors in spellings as well as tenses in several pages. The blame may not be with the author, but should be put on the table of the humanities editor of Parresia publishers. When the author hypothesises that, “Now, if anything Akan is proud of, it is the fact that he was and remains a village boy. Next to that is the knowledge that Grandma and Maama’s God is true and does raise people from nothing to something, from nowhere to somewhere, from grass to grace, from victims to victors, from obstacles to miracles, from trials to triumphs, from poverty to prosperity and from manger to mansion,” I dare say that the Village Boy is a must read for all and sundry, especially as a secondary school text, for the development of the capacity to withstand untoward circumstances, remain focused and dream of redemption some day and yet still remain one’s self.

Village Boy betrays the prospects of not remaining in a print form only and in multiple languages for that matter, but other formats of presentation including drama. There is the surge of a deafening rave that the Village Boy in a feature film format stands to be a blockbuster and box office grosser. The cartoon version of the book cannot but be a children’s delight. This book, written in fluid fireside story-telling style is unputdownable as it plays the tour guide on the journey from grave to grass to grace; unlocks the forces immanent in each of us and a trajectory to personal fulfilment if we dare.

I endorse the Village Boy for every village boy and girl for its nostalgic and therapeutic capital as a modern lore and as we all hail from villages.

Udoka is a Scholar-Artiste, Choreographer, Writer and Winner 2010 Association of Nigerian Authors NDDC J. P. Clark Drama Prize and Nominee 2014 NLNG Literature Prize.

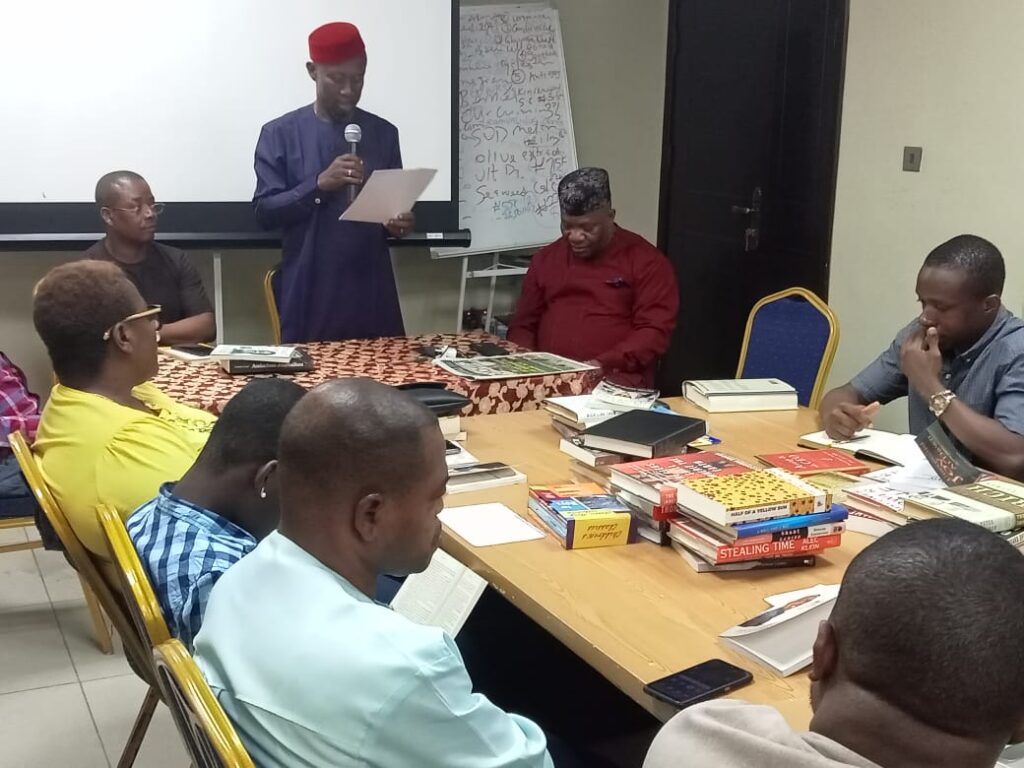

This review was organized by Uyo Book Club to mark the one-year anniversary of the Village Boy launch.

Concluded